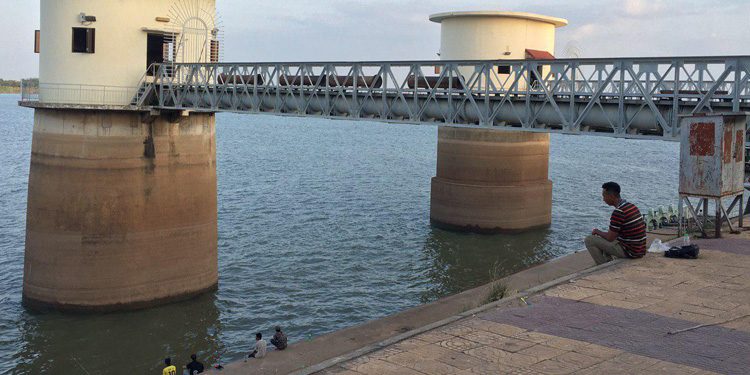

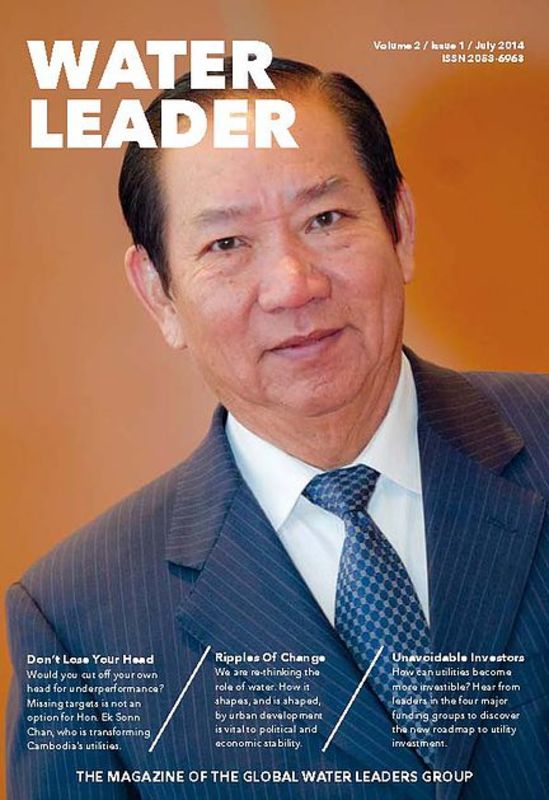

Asia’s urban multitudes are thirsty and ever-growing. Providing them with safe drinking water is a gargantuan task everywhere. But consider Phnom Penh. The Cambodian capital and former French colonial center had only a modest water distribution system, to begin with. Bombing, civil war, and social havoc in the early 1970s brought waves of refugees to the city. Then, abruptly in 1975, the triumphant Khmer Rouge banished every person from Phnom Penh and abandoned its already sagging infrastructure to atrophy. When the genocidal regime was driven from power in 1979, the city swelled again, yet little was done to revive its broken-down water system. Then, in 1993, Ek Sonn Chan was put in charge.

As a young engineering graduate, Ek Sonn Chan lost his entire family to the killing fields of the Khmer Rouge. He managed to survive as a farmer. In 1979, he found work at the Phnom Penh municipal abattoir and subsequently rose to be the city’s director of commerce. The water system he inherited in 1993 was barely a system at all. Over the years, its ancient French-laid pipes had been augmented haphazardly into an indecipherable maze of connections. No blueprints had survived the Khmer Rouge, nor had the engineers who understood them. The entire labyrinth was riddled with holes and so porous that disease-laden sewage easily seeped in. Ek discovered that 70 percent of the city’s water was lost to leaks or theft. Among the thieves were his own employees as well as military men and other VIPs who profited by selling water to better-off neighborhoods. Poor people paid black marketeers dearly for what was left. The city’s water agency collected fees from only half its users. Not surprisingly, it was losing money.

Ek combed his bloated workforce for the best and brightest and set them to work–locating and repairing the system’s myriad leaks, installing thousands of water meters, and closing hundreds of illegal connections. He installed a computerized billing program, financed by France, and persuaded other international lenders that his agency was a good risk. In 1997, the Phnom Penh Water Supply Authority (PPWSA) became an autonomous public enterprise. With major loans from the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, and the government of Japan, General Director Ek Sonn Chan embarked upon a major overhaul.

He laid 1,500 kilometers of new pipelines and expanded the Authority’s water output by 600 percent. He confronted VIP nonpayers and cut off their water when persuasion failed, achieving a collection rate of 99 percent by 2003. He raised prices, resulting in strong revenues and an enviable reputation for paying the Authority’s debts ahead of schedule. With pricing policies favoring light users as well as subsidized connection fees and installment payment plans, he made cheap water available to the city’s poorest neighborhoods. New and refurbished water-treatment plants ensured that this water met WHO water safety standards. At the same time, Ek professionalized the Authority’s workforce, building its technical capacity and instilling in its employees a work ethic of discipline, competence, and teamwork.

Today, Ek’s clean water reaches virtually all of Phnom Penh’s inner city and he is busy spreading it to the outer reaches of the metropolis. In 2004, the World Bank cited PPWSA for its “dramatic improvement in organization, profitability and organizational performance.”

Ek Sonn Chan attributes his drive to “work for the country” to the traumas of Cambodia’s recent past. Patriotism also explains his preference for public utilities over private-sector ones. “The profit made by us,” he says, referring to the Phnom Penh Water Supply Authority, “will be profitable for our country.”

In electing Ek Sonn Chan to receive the 2006 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Government Service, the board of trustees recognizes his exemplary rehabilitation of a ruined public utility, bringing safe drinking water to a million people in Cambodia’s capital city.

According to rmaward.asia