The founding figure of this organisation, Kommaly Chanthavong, was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize in 2005 for her work in support of women’s right to a stable and dignified source of income and was given the Ramon Magsaysay award for her passion of silk weaving revived and developed the ancient Laotian art, creating livelihoods for thousands of poor and war-displaced Laotians.

Born in 1950, she learned weaving from her mother at the age of six. When she was 11 years old, she fled her village after it was destroyed by a US bomber during the Laotian Civil War. Chanthavong walked across her country for over a month, finally reaching safety in its capital Vientiane.

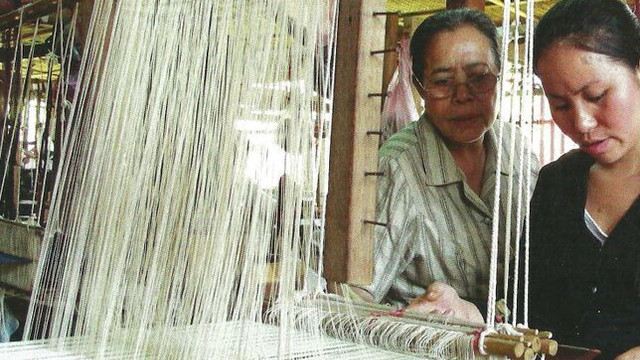

Having witnessed first-hand the devastation brought by conflict, she set out to help displaced women and their families by teaching them how to weave silk. She eventually founded a silk weaving cooperative with ten members, the Phontong Handicraft Cooperative, which has now grown to employ over 450 people across 35 villages, and later founded Mulberries.

A circular process

One of the founding missions of Mulberries is to bring environmental sustainability to the lives of rural Laotian people. To achieve this, The Lao Sericulture Company uses a cyclical process of silk production that supports village life. “The quantity we produce each month depends on the complexity of the weaving patterns,” Vosinthavong explains. At any given time, Mulberries raises between 600,000 and 900,000 baby silkworms in its farm in Xieng Khouang province, in north-eastern Laos. “Our raising season starts from April to November,” Vosinthavong says. “We raise approximately five to six times per year. We distribute the majority of these baby worms to our producers (in a radius of approximately 60 to 200 kilometres). For villages that are over 250 kilometres away, we generally send them the silk eggs for them to raise directly”.

The key to this operation are the mulberry trees themselves: their leaves are used as organic fertiliser and food for silkworms, their bark is employed to make tea and the fruits are used to create dyes and as food. In addition, when grown correctly, these plants can help prevent soil erosion and rejuvenate the earth. The cycle doesn’t end here, as nearly everything is used and recycled. The silkworms that produce silky cocoons also generate nutrient rich waste. On top of this, the pupae (the insects in their metamorphosis stage) are enjoyed as a food source high in protein.

Moving along the process, we come to the transformation of the cocoon into silk threads and here too, waste is minimized. The unusable exterior parts of the cocoon are reinvented as stuffing for blankets and pillows. The silk water used to soften and clean the silk threads then becomes a prized skin moisturizer.

To ensure an environmentally sustainable product, all-natural components are grown organically. This includes the production of natural dyes made from locally grown plants such as indigo, tamarind and coffee beans, to name a few.

The importance of Mulberries’ work

Mulberries doesn’t only help local people access a sustainable source of livelihood, it also promotes traditional arts. Both silk weaving and natural dyeing are age-old traditions passed on through generations of Laotian women. “For more complex patterns one piece can require up to two or four months,” says Vosinthavong. Its products, therefore, represent more than just clothing and an occupation, they’re an art form connected to a traditional way of living. With modernity, such forms are becoming increasingly rare and must be protected, and Mulberries represents a great example of how a company can do so whilst promoting social and environmental sustainability.

According to lifegate.com